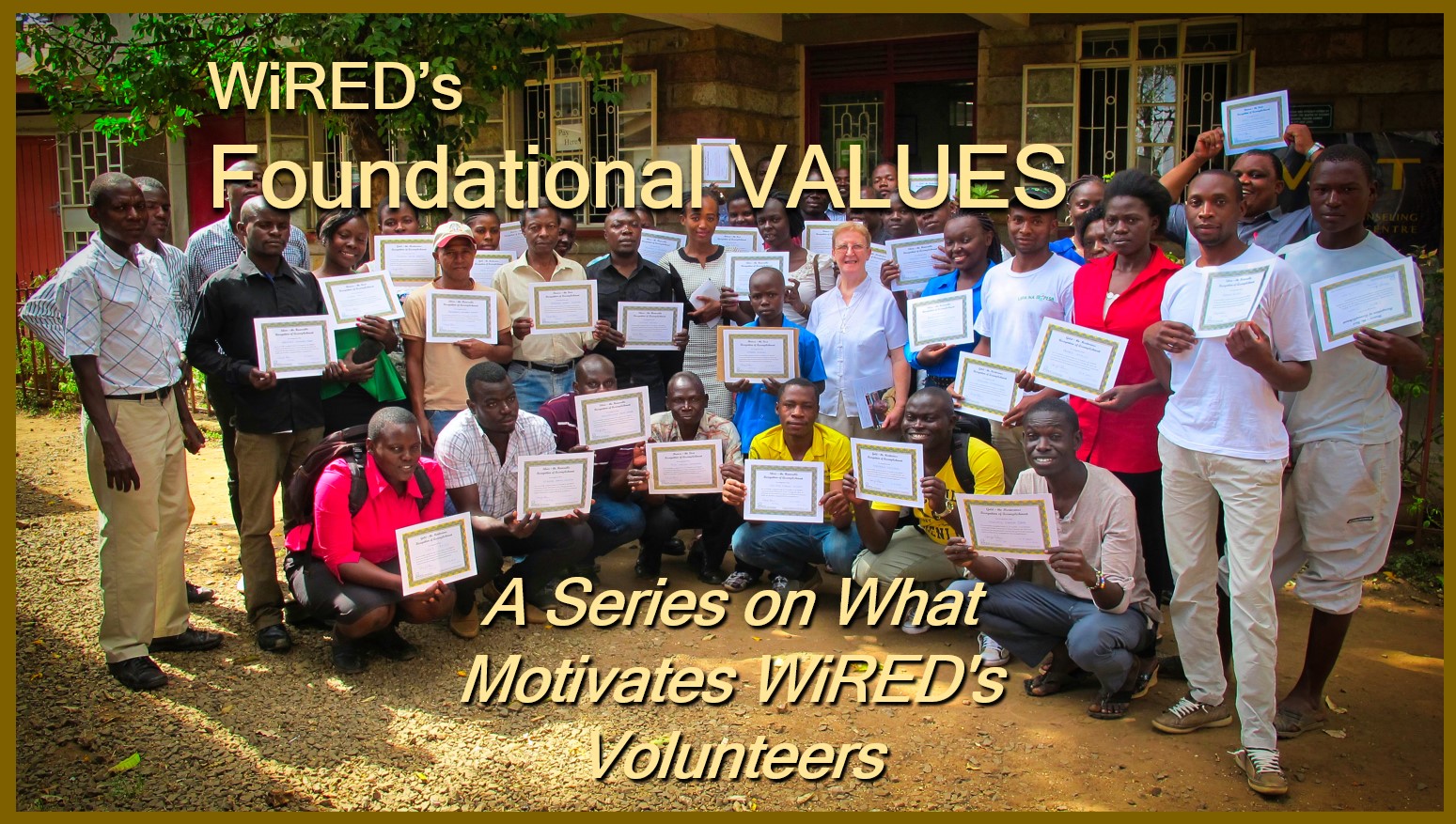

Introduction to A Series Exploring The Values That Have Driven WiRED’s Volunteers for Nearly 30-years.

By Gary Selnow; Edited by Elizabeth Fine

For nearly 30 years, WiRED’s volunteers have been providing health education to underserved communities around the world. In the coming months, we will reflect on a selection of our programs and activities that exemplify the core values and principles that have guided our work over the years.

For nearly 30 years, WiRED’s volunteers have been providing health education to underserved communities around the world. In the coming months, we will reflect on a selection of our programs and activities that exemplify the core values and principles that have guided our work over the years.

WiRED’s operations have evolved alongside medical research advances since the 1990s, allowing healthcare workers to stay abreast of the latest disease prevention and treatment methods. We also have embraced technological advancements, from early floppy drives to modern internet-based tools that facilitate global distribution of our training programs.

WiRED’s operations have evolved alongside medical research advances since the 1990s, allowing healthcare workers to stay abreast of the latest disease prevention and treatment methods. We also have embraced technological advancements, from early floppy drives to modern internet-based tools that facilitate global distribution of our training programs.

![]() While our methods have changed to reflect medical and technology developments, what has not changed is our unwavering commitment to our mission and to the people we serve. What has not changed is our foundational values that guide our work and motivate our selfless volunteers. These values help explain the drives of ordinary people to volunteer their time and skills to improve the health of communities often forgotten by large institutions and organizations.

While our methods have changed to reflect medical and technology developments, what has not changed is our unwavering commitment to our mission and to the people we serve. What has not changed is our foundational values that guide our work and motivate our selfless volunteers. These values help explain the drives of ordinary people to volunteer their time and skills to improve the health of communities often forgotten by large institutions and organizations.

As we approach our 30th year, we will present stories from our archives and essays written by our volunteers. Each piece offers insights into the motivations that compel our team to work for the benefit of distant populations.

As we approach our 30th year, we will present stories from our archives and essays written by our volunteers. Each piece offers insights into the motivations that compel our team to work for the benefit of distant populations.

We begin with a graduation speech by WiRED’s founder, Gary Selnow, delivered at San Francisco State University in 2004. This speech outlines a philosophy of community and service that has shaped our organization for many years.

We begin with a graduation speech by WiRED’s founder, Gary Selnow, delivered at San Francisco State University in 2004. This speech outlines a philosophy of community and service that has shaped our organization for many years.

San Francisco State University Graduation

May 29, 2004

Context for the following speech:

By 2004 WiRED had established health training programs across the Balkans and in Africa, Central America and Iraq. Notably, these efforts were entirely volunteer-driven, with dedicated individuals from around the world providing training to communities they might never personally encounter. This address to San Francisco State University’s graduating class explores the inspiring principles that united WiRED’s team of volunteers and fueled their commitment to improving global health.

The war in Iraq, referenced in this speech, was raging at the time with the death toll to American and Allied troops and to Iraqi people mounting by the day. The war caused rifts within the American population, still suffering from the impact of the 2001 bombings in New York City and the devastation taking place in Iraq. The war was initiated based on claims of Iraqi complicity in the September 11th attacks, which were later discredited.

The war in Iraq, referenced in this speech, was raging at the time with the death toll to American and Allied troops and to Iraqi people mounting by the day. The war caused rifts within the American population, still suffering from the impact of the 2001 bombings in New York City and the devastation taking place in Iraq. The war was initiated based on claims of Iraqi complicity in the September 11th attacks, which were later discredited.

_________________________________

The Speech

Thank you, President Corrigan, for this invitation to speak to this year’s graduating class. I’m happy to offer a few thoughts that reflect on the efforts of the gifted, generous and caring people who work with me at WiRED.

Volunteers are the heart and soul of WiRED. They assist nurses and doctors in the battle against the ravages of diseases like AIDS; they supply computers to students in the world’s poorest regions to help them pull alongside their brothers and sisters in more affluent countries. From Africa to the Balkans, Nicaragua to the Middle East, these tireless volunteers provide people, who are often forgotten, with encouragement, information and hope. To illustrate, in Iraq alone, more than 5,000 doctors and medical students update their scientific knowledge at our electronic libraries. All that is good in itself, but it also has a second practical pay-off: Like casting bread upon the waters, it comes back to us by helping shore up America’s image abroad. Sadly, today, our nation’s image is not good.

To illustrate, in Iraq alone, more than 5,000 doctors and medical students update their scientific knowledge at our electronic libraries. All that is good in itself, but it also has a second practical pay-off: Like casting bread upon the waters, it comes back to us by helping shore up America’s image abroad. Sadly, today, our nation’s image is not good.

Professor Joseph Nye at Harvard says that among our nation’s greatest strengths are our compassion, drive and generosity for people abroad. American volunteers and their humanitarian work develop friendships and cultivate trust — and these build goodwill which lies at the core of sound foreign relations. Last year, I was reminded of how much volunteer power means to America while flying back from my first trip to Baghdad. I had hitched a ride on a military plane — and there, just across from me, was the flag-draped body of a young American soldier killed in action. He was probably about the age of many graduates here today, surely no older than many of our volunteers.

Last year, I was reminded of how much volunteer power means to America while flying back from my first trip to Baghdad. I had hitched a ride on a military plane — and there, just across from me, was the flag-draped body of a young American soldier killed in action. He was probably about the age of many graduates here today, surely no older than many of our volunteers.

Seeing that soldier brought to mind the two fronts in the war we are fighting today — one fought with a clenched fist — the other with an out-stretched hand. The first is military, the second humanitarian. The military battle began on September 11, 2001, surely one of the darkest moments in American history. That was a terror strike on the innocent, and Americans reacted as we inevitably had to. We drew our swords, clenched our fists, and attacked an enemy that vowed to destroy us. That war took us to Afghanistan.

The military battle began on September 11, 2001, surely one of the darkest moments in American history. That was a terror strike on the innocent, and Americans reacted as we inevitably had to. We drew our swords, clenched our fists, and attacked an enemy that vowed to destroy us. That war took us to Afghanistan.

Then came Iraq. Iraq was not the caldron of terrorism that it appears to be today. Indeed, our fight there seems not so much to have reduced terror, as to have engendered it. We fight terrorism now almost entirely with the fist.

Meanwhile, our friends have stepped back from us, while our enemies gather in a thousand shadows. Nourished by fear and resentment they grow in strength and number. We called out the soldiers on September 11th — if only we had called on ALL Americans. We could have summoned the humanitarian forces of teachers and scientists and entrepreneurs, students and builders, shopkeepers and writers. Their talents applied through the Peace Corps, Habitat for Humanity, the Fulbright program and a multitude of small humanitarian organizations like WiRED, would show the world that in helping there is strength — in compassion, generosity and sharing there is power.

We called out the soldiers on September 11th — if only we had called on ALL Americans. We could have summoned the humanitarian forces of teachers and scientists and entrepreneurs, students and builders, shopkeepers and writers. Their talents applied through the Peace Corps, Habitat for Humanity, the Fulbright program and a multitude of small humanitarian organizations like WiRED, would show the world that in helping there is strength — in compassion, generosity and sharing there is power.

Humanitarian responses — sometime chided as soft-headed — can be among America’s greatest strategies against terrorism. In truth, nothing would do more to temper terrorism than sharing the wealth, the knowledge, the resources that flood the shadows with light and strike hard against the terror-seeds of ignorance, disease and poverty. Being a professor, I have a compulsion to give advice. Lord knows, you have had too many years of professorial advice, but I’ll ask you to bear just a little more of it. To the graduates sitting here today, let me say that, more than ever, this great country needs you. In the global war on terror, you might not take up the sword, but you can offer up your human talents — your professional skills, your youthful energies and enthusiasm. In this new war, the battlefields are the clinics and shops, classrooms and operating rooms, stadiums and union halls.

Being a professor, I have a compulsion to give advice. Lord knows, you have had too many years of professorial advice, but I’ll ask you to bear just a little more of it. To the graduates sitting here today, let me say that, more than ever, this great country needs you. In the global war on terror, you might not take up the sword, but you can offer up your human talents — your professional skills, your youthful energies and enthusiasm. In this new war, the battlefields are the clinics and shops, classrooms and operating rooms, stadiums and union halls. Orator Robert Ingersoll said: “If the naked are clothed; if the hungry are fed; if justice is done; . . . if the defenseless are protected . . . all must be the work of people. The grand victories of the future must be won by humanity and by humanity alone.”

Orator Robert Ingersoll said: “If the naked are clothed; if the hungry are fed; if justice is done; . . . if the defenseless are protected . . . all must be the work of people. The grand victories of the future must be won by humanity and by humanity alone.”

If some of you in this remarkable class of 2004 were to join that human army, what wonderful news that would be for a hurt and broken world.