By Gary Selnow, Ph.D., Executive Director

A small film crew and I flew out of the Kisumu airport in mid-February 2020. For several weeks, we had been observing a new training program for community health workers (CHWs) in western Kenya. Later that year, the new graduates would put on their CHW T-shirts and badges and deploy to the poorest sections of town, the informal settlements, often called slums.

COVID-19 strikes

COVID was in the news back then, but mostly as a curiosity, not as a threat. That quickly changed. A week after the film crew and I got back to California, the number of COVID infections began rising in the United States and abroad, elevating concerns among public health officials and medical experts. And yet, many of us didn’t take COVID as seriously as we should have; a convenient theory held that it would all go away with the arrival of warm weather in spring.

COVID was in the news back then, but mostly as a curiosity, not as a threat. That quickly changed. A week after the film crew and I got back to California, the number of COVID infections began rising in the United States and abroad, elevating concerns among public health officials and medical experts. And yet, many of us didn’t take COVID as seriously as we should have; a convenient theory held that it would all go away with the arrival of warm weather in spring.

As everyone now knows, COVID did not go away. By early March, hospital admissions and death tolls rose, businesses shuttered their doors, governments introduced travel controls to stem the spread of the mysterious disease. No matter, COVID relentlessly tightened its grip, and, by mid-March, countries around the world grew more alarmed and closed borders to all but essential travel. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) published guidelines for management of the outbreak urging such measures as testing, case isolation and mask wearing.[1] Meanwhile, without missing a beat, hucksters pushed phony elixirs and cures, few of them effective, some of them causing illness and death. [2] White House experts predicted more than 200,000 U.S. COVID deaths. They missed the mark by a mile: in the years ahead, over 1.1 million Americans would die from the virus;[3] 7 million people would die globally, and it isn’t over yet.[4]

Back in Kisumu

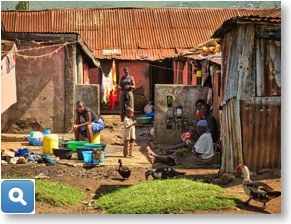

East Africa initially experienced a lower COVID death rate than most other places, largely it is believed because of a much younger population.[5] Nonetheless, East Africans were not spared from the virus, which killed thousands of people.[6] Communities became frightened and holed up in fear. Bewildered governments desperately followed WHO’s guidelines to minimize the spread of disease. Doctors struggled as patients sick with COVID packed hospital corridors. Treating patients depended on elaborate equipment hospitals often could not afford and antiviral drugs they could not access for more than a year. Desperate for a treatment, doctors tried whatever drugs they had on the shelf, such as medicines for Ebola, malaria and HIV, all with limited effect.[7] Poverty, a cruel and persistent second plague in this part of the world, made battling COVID even tougher.[8]

The rising number of COVID patients placed enormous strain on medical professionals themselves. In addition to imposing stress and burnout, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) reports that COVID was the third leading cause of death among medical workers.[9] As a result, decreasing numbers of doctors and nurses treated growing numbers of very sick patients. COVID assaulted the world’s medical communities from all directions.[10]

The rising number of COVID patients placed enormous strain on medical professionals themselves. In addition to imposing stress and burnout, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) reports that COVID was the third leading cause of death among medical workers.[9] As a result, decreasing numbers of doctors and nurses treated growing numbers of very sick patients. COVID assaulted the world’s medical communities from all directions.[10]

In late March, WiRED International’s U.S.-based staff released a training module explaining what science understood at the time about COVID: transmission, prevention and whatever little we knew about treatment. Our CHWs in Kisumu, although not yet deployed, downloaded the module and studied it on their phones. Within hours they knew as much, and probably more, about the disease as paraprofessional health workers anywhere.[11]

Back in the U.S., we at WiRED watched in horror the news about COVID hitting low-resource communities whose frail healthcare systems strained from the burden of this demanding illness. It was clear that we had to consider deploying the new CHWs much sooner than we — or they — planned. These young people had been fully trained in community infection control. They knew about viral diseases, how these diseases spread, how airborne pathogens infect, how prevention measures slow person-to-person transmission.[12] And so, with an urgent request, we reached out to donors who provided funds to deploy the CHW team (at that point 18 people) for a half year, covering modest salaries and expenses for equipment and supplies.

Back in the U.S., we at WiRED watched in horror the news about COVID hitting low-resource communities whose frail healthcare systems strained from the burden of this demanding illness. It was clear that we had to consider deploying the new CHWs much sooner than we — or they — planned. These young people had been fully trained in community infection control. They knew about viral diseases, how these diseases spread, how airborne pathogens infect, how prevention measures slow person-to-person transmission.[12] And so, with an urgent request, we reached out to donors who provided funds to deploy the CHW team (at that point 18 people) for a half year, covering modest salaries and expenses for equipment and supplies.

I contacted Lillian Dajoh, our manager in Kisumu, to discuss a deployment strategy. Could the CHWs deploy early? How did they feel about working in communities hit by COVID? What could we do to assist the population and keep our CHWs safe from infection? We held give-and-take briefings with CHWs, came up with a good plan, purchased the equipment and supplies and then put the plan into play. Deploying much earlier than anyone planned, our CHWs went into the poorest parts of town to provide clinical services and to teach local people how to protect themselves from the virus.

I contacted Lillian Dajoh, our manager in Kisumu, to discuss a deployment strategy. Could the CHWs deploy early? How did they feel about working in communities hit by COVID? What could we do to assist the population and keep our CHWs safe from infection? We held give-and-take briefings with CHWs, came up with a good plan, purchased the equipment and supplies and then put the plan into play. Deploying much earlier than anyone planned, our CHWs went into the poorest parts of town to provide clinical services and to teach local people how to protect themselves from the virus.

It’s important to note that while COVID loomed, other health conditions did not relent and continued hammering these poor communities.[13] People still contracted malaria, HIV/AIDS, cholera and TB. Women still faced pregnancy complications, and parents still worried about children who became injured and ill. Hunger, a persistent specter in this part of the world, was made so much worse by historic droughts, locust and crop disease.[14] The CHWs addressed as many health conditions as anyone could; their hands were full.

Three years later — my visit in September 2023

During my last meeting with the group, I recall wishing the students well as I left for the airport and they headed back to class after a lunch break. In two weeks they would wrap up their training, take final exams and receive their certificates. They would be proud new CHWs, wet behind the ears.

Jump ahead to September 2023. With several years of service under their belts, the young CHWs had become seasoned veterans.[15] Their training, starting in a classroom, became supercharged in the field. Now they understood so much more about the operational mechanics of community health work — the things we can’t teach in a classroom. This second portion of their training was a baptism in fire.

Throughout the COVID pandemic, I stayed in close touch with members of our team by way of email, WhatsApp and Zoom, tracking their progress and responding to their needs for supplies, equipment and other resources. Every month, Lillian, our manager, sends WiRED’s U.S. team a report on the CHW activities, which we summarize and post on our website. Even with this constant flow of information, it wasn’t until I sat across the table from these young people and heard their stories firsthand that I really understood their heroic work.

Throughout the COVID pandemic, I stayed in close touch with members of our team by way of email, WhatsApp and Zoom, tracking their progress and responding to their needs for supplies, equipment and other resources. Every month, Lillian, our manager, sends WiRED’s U.S. team a report on the CHW activities, which we summarize and post on our website. Even with this constant flow of information, it wasn’t until I sat across the table from these young people and heard their stories firsthand that I really understood their heroic work.

At the start of this project, I believed that if we supplied a rigorous curriculum taught by local medical professionals, CHWs would develop the knowledge and skills they needed to provide a wide range of health services to people in underserved communities. These young people far exceeded my expectations. Consider that each month around 20 CHWs provide basic clinical services and health training programs to more than 9,500 community members!

At the start of this project, I believed that if we supplied a rigorous curriculum taught by local medical professionals, CHWs would develop the knowledge and skills they needed to provide a wide range of health services to people in underserved communities. These young people far exceeded my expectations. Consider that each month around 20 CHWs provide basic clinical services and health training programs to more than 9,500 community members!

Much to their credit, even while the CHWs were working in the field, they continued to expand their “book knowledge” by way of continuing medical education, a program WiRED provides online. They also took additional training on the distribution and delivery of COVID vaccines. So, in the middle of the pandemic, they continued to develop new skills that would increase their value to the community.[16]

Final thoughts

It would be difficult to overstate my admiration for these CHWs. They strengthened their communities by playing a key role in addressing the pandemic and other health issues threatening these vulnerable populations. They have been effective, in part, because they come from the communities they serve. As sons and daughters of these informal settlements, they are able to engage the population in ways not possible for doctors or nurses from the outside. Community health is about medical interventions, yes, but it involves so much more. Especially during a crisis like the pandemic, the labors of health workers demand empathy, trust, familiarity with the social structure and with the challenges of poverty. CHWs, trained properly in community health basics, can assist in ways that outsiders cannot.

During the past three years — through clinical work, teaching, monitoring people who were ill and referring people who needed higher-level care — these CHWs have contributed valiantly to these low-resource communities. Beyond the many services they continue to provide, they validate every day the essential role of health paraprofessionals in underserved regions. These CHWs have done their part. They have contributed to the health of the people. My hat is off to these young community health workers.

During the past three years — through clinical work, teaching, monitoring people who were ill and referring people who needed higher-level care — these CHWs have contributed valiantly to these low-resource communities. Beyond the many services they continue to provide, they validate every day the essential role of health paraprofessionals in underserved regions. These CHWs have done their part. They have contributed to the health of the people. My hat is off to these young community health workers.

[1] Strong social distancing measures in the United States reduced the COVID-19 growth rate. (2020). Health Affairs, Vol. 39, NO. 7. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00608#:~:text=State%20and%20local%20governments%20imposed,disease%20(COVID%2D19).

Timeline: WHO’s COVID-19 response. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline

[2] Coronavirus scammers are flooding social media with fake cures and tests. https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/4/17/21221692/digital-black-market-covid-19-coronavirus-instagram-twitter-ebay

[3] https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#deaths-landing

[4] https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/about/

[5] Media age in the world is 30.5 years. https://www.worldometers.info/demographics/world-demographics/#median-age. Median age in Africa is 18.8 years. https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/africa-population/#:~:text=Africa%20Population%20(LIVE)&text=The%20population%20density%20in%20Africa,128%20people%20per%20mi2).&text=The%20median%20age%20in%20Africa%20is%2018.8years

[6] https://preventepidemics.org/covid19/science/insights/update-on-covid-19-in-africa/

[7] Kim P, Read S, Fauci A. Therapy for early COVID-19: A critical need. (2020). JAMA. Published online November 11, 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.22813

[8] https://www.brookings.edu/articles/covid-19-is-a-developing-country-pandemic/

[9] Smith DK, Al-Hasani A, Lee K, & Friese CR. (2021). Leading causes of death among U.S. healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA, 325(24), 2478-2480.

[10] https://www.who.int/news/item/02-05-2023-new-survey-results-show-health-systems-starting-to-recover-from-pandemic

[11] COVID was drawing the attention of public health officials in the second half of 2019, although few predicted the serious impact it eventually would have. Several years earlier with similar concerns during the early days of Ebola, Zika and polio, WiRED released training modules to familiarize health communities with those diseases. When we saw that COVID, too, posed a real problem, we developed a module reviewing whatever was known about the virus and its potential for global disruption. After the scope of the pandemic became evident, we synthesized CDC and WHO information and presented the outcome as a second, more complete module.

[12] Included in WiRED’s comprehensive CHW basic training curriculum are these modules directly related to COVID: Understanding Communicable Diseases, 2 parts; Infection Prevention and Control; Infectious Disease Control, The Role of CHWs; Mode of Transmission: Airborne Infectious Diseases; Mode of Transmission: Direct Contact Infectious Diseases; Emerging Infectious Diseases for Community Health Professionals; Health Promotion and Disease Prevention; Health Surveillance Skills.

[13] National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information. The impact of COVID-19 on communicable and non-communicable diseases in Africa: a narrative review. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35350264/

[14] https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/locust-upsurge-east-and-horn-africa-final-report-n-mdr60005-15-february-2022

Kenya: Drought, 2014-2023. https://reliefweb.int/disaster/dr-2014-000131-ken

[15] In 2022, we held a second four-week training session to bring in additional CHWs. Some people from the new group joined the original CHWs, several of whom had to drop out because of illness and family issues. Consequently, some people have been in the field for one and a half years while the original group has been serving for more than three years.

[16] In addition to our CHWs in Kenya, we also provided training for vaccine distribution and delivery in Liberia and Uganda.