By Gary Selnow, Ph.D.

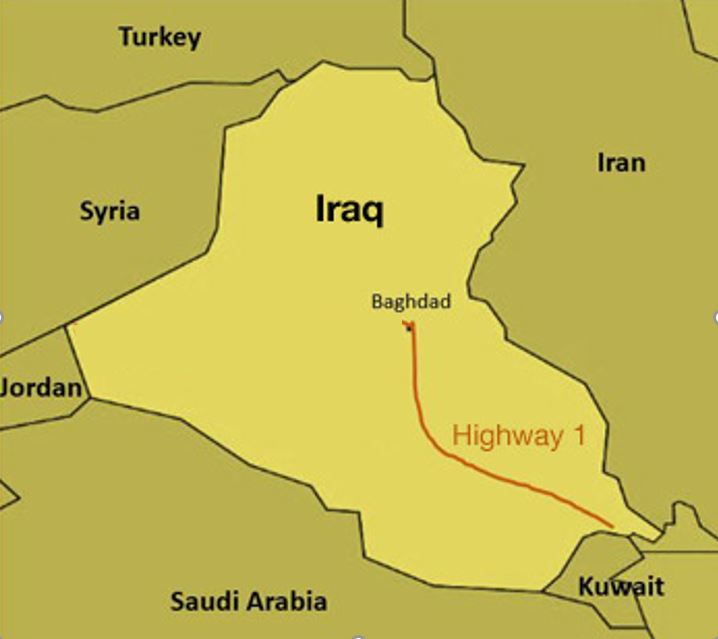

Twenty years ago this month, I left for Iraq, arriving in the wake of American troops who, several weeks earlier, had launched Operation Iraqi Freedom. The first stop was Kuwait, where I joined up with a U.S. State Department official. We left early the next day, in a three-car convoy organized by Navy Seals, driving north on Highway One to Baghdad. By mid-afternoon, our small group arrived in the Green Zone and Saddam’s Republican Palace, an enormous, garish structure that was transforming into the headquarters of American operations in Iraq.

Twenty years ago this month, I left for Iraq, arriving in the wake of American troops who, several weeks earlier, had launched Operation Iraqi Freedom. The first stop was Kuwait, where I joined up with a U.S. State Department official. We left early the next day, in a three-car convoy organized by Navy Seals, driving north on Highway One to Baghdad. By mid-afternoon, our small group arrived in the Green Zone and Saddam’s Republican Palace, an enormous, garish structure that was transforming into the headquarters of American operations in Iraq.

The State Department official, Jim Mollen, was head of the Global Technology Corps (GTC), a State Department program exploring the use of computer technology to advance public diplomacy around the world. 2003 was still the early days of computer technology. Google was just a toddler. Laptops were as thick and heavy as the New York City phone book. Dial-up modems, loud and slow, connected users ploddingly to the Internet. In time, these seeds would grow; technology showed enormous potential.

The GTC was in Iraq to explore how the United States could bring these promising technologies to bear on the country’s reconstruction. Jim’s passion was to spark Iraq’s neglected educational system with a jolt of IT tools in classrooms and libraries. I was there to build an IT bridge between Iraq’s medical community and medical resources outside the country.

For reasons hard to grasp, in the mid-1980s, Saddam Hussein began suffocating the Iraqi medical community. He cut off contact with outside medical resources. He prohibited travel to medical conferences and halted delivery of medical journals and textbooks. Medical students showed me their “textbooks,” which were faded photocopies of photocopies of books published two decades earlier. As a result of the isolation, the Iraqi medical community, desperate to maintain its once glowing reputation, slowly watched its capacities wither like a tree wasting in the Iraqi desert. The practice of medicine in Iraq reaches back to the ancient laws of Hammurabi, who lived in Babylon in the first millennium BC. And now, in 2003, that venerated medical community suffered at the hands of a tyrant who used isolation to torment his doctors, confident their diminishing capacities would punish his people.

For reasons hard to grasp, in the mid-1980s, Saddam Hussein began suffocating the Iraqi medical community. He cut off contact with outside medical resources. He prohibited travel to medical conferences and halted delivery of medical journals and textbooks. Medical students showed me their “textbooks,” which were faded photocopies of photocopies of books published two decades earlier. As a result of the isolation, the Iraqi medical community, desperate to maintain its once glowing reputation, slowly watched its capacities wither like a tree wasting in the Iraqi desert. The practice of medicine in Iraq reaches back to the ancient laws of Hammurabi, who lived in Babylon in the first millennium BC. And now, in 2003, that venerated medical community suffered at the hands of a tyrant who used isolation to torment his doctors, confident their diminishing capacities would punish his people.

WiRED’s Program Takes Shape

Within a day of arriving in Baghdad, I met Steven Browning, an American engineer with the Office for Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance, serving as the Senior Advisor/Acting Minister for the Ministries of Health. I didn’t need to convince Steve about the potential of our work. He knew full-well that upgrading the capacity of Iraqi doctors depended on fortifying their relationships with medical communities outside the country.

Initially, my efforts concentrated on Baghdad’s Medical City Center, the largest medical complex in the country. Medical City housed 17 integrated medical facilities, including a medical school, medical libraries and a teaching hospital. By all measures, it was the logical place to start.

Initially, my efforts concentrated on Baghdad’s Medical City Center, the largest medical complex in the country. Medical City housed 17 integrated medical facilities, including a medical school, medical libraries and a teaching hospital. By all measures, it was the logical place to start.

Academics like to study things to death, but in real-life Iraq at the time, we had to gather information quickly, come up with the best plan possible with the best evidence available and speed the plan into action.

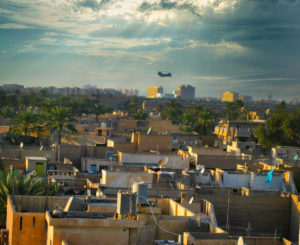

Information gathering was difficult. Iraq had no cell phone service and landlines were down, so all discussions, negotiations and deals had to be done in person. We became snarled in massive traffic jams on our way to meetings with physicians, administrators and medical students. I mostly traveled without security, so I hired a local used car dealer to drive me. Each morning, he would select from the worst, battle-scarred vehicles on the lot, tape up the windows and pick me up for the day’s travel. Clunkers blended in with the swarm of other clunkers on the road and taped-up windows, fitting for the overall condition of the car, obscured me from those who might be curious about its passenger.

We visited as many medical professionals and nearby hospitals as time allowed, and when we sized up the data, we knew everything we needed to know about the continuing medical information needs of the Iraqi doctors. We might well have skipped it all and saved the time: they needed everything. For years, the tight grip of Saddam’s hands on the throats of Iraq’s doctors effectively choked off their access to the outside world.

We visited as many medical professionals and nearby hospitals as time allowed, and when we sized up the data, we knew everything we needed to know about the continuing medical information needs of the Iraqi doctors. We might well have skipped it all and saved the time: they needed everything. For years, the tight grip of Saddam’s hands on the throats of Iraq’s doctors effectively choked off their access to the outside world.

That 20-year lockdown denied Iraqi doctors even basic information sources, such as a World Health Organization innovation called HINARI. This hugely popular, global program allowed physicians in low-resource countries free access to hundreds of current medical journals and books. But, to get HINARI, you had to apply to Geneva, and you needed Internet access. And so, Iraqi doctors suffered a double-whammy: they were not allowed to apply for anything, and they didn’t have the Internet. I put HINARI high on our acquisition list.

Recognizing the dire need for medical updates, we formed a plan to bring in as much information as possible, as quickly as possible, and backfill later with a richer set of resources. Our plan called first for a computer workroom in Medical City Center. In the weeks after completing the Medical City facility we would outfit additional centers in several hospitals around Baghdad. These workrooms or, as we called them, Medical Information Centers (MICs), or Centers, would immediately offer digital libraries, which we would carry in physically on CD-ROMs, and as soon as possible afterwards provide the Internet through satellite connections arranged by the Americans.

In the United States, it would have been easy to buy the computers, wire them into a network, connect the network to the Internet and throw the switch. But, in Iraq in the spring of 2003, there were no computers, no techs to wire them up and no Internet. In this essay, I discuss how we obtained all the items on our shopping list.

The First Medical Information Center

A little more than a month after we sketched out the plan, we launched the first 12-station computer facility in Medical City Center. We held a party. Doctors and medical students packed into the room for the grand opening celebration. A crowd of officials also showed up even though most of them knew little about the project. There wasn’t much in Iraq to celebrate back then, so an event that might otherwise have gone unnoticed drew a crowd, and unsurprisingly compiled a long roster of speakers who shared credit for the project. Success has many fathers. Those of us who actually worked on the Center were happy to share success; it was the first bridge to link Iraq’s beleaguered medical community with the world outside.

Within several months, we installed seven more computer centers in Baghdad-area hospitals. One was in the National Spinal Cord Injury Center, funding for which was provided by the Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation. On Monday, August 19, 2003 a massive explosion at the United Nations building killed 22 people, destroyed the UN building and severely damaged the nearby Spinal Cord facility and our Center. It was the first of our Centers to fall to insurgents.

The Medical Community, Targeted

Over the next three years, we outfitted 39 centers in Iraq, including nine in the Kurdish region in northern Iraq. From time to time, we would get word that a computer facility elsewhere in the country was shot up or taken out by an insurgent’s bomb. The loss of a Center was a setback, but the real loss to Iraq during those tumultuous years was the death of more than 2,000 doctors, killed not only in hospitals and clinics but in their homes and in the streets on their way to work.

A tragic example is a friend and colleague, Dr. Khalid Mayah, director of the Basra Teaching Hospital. Early in WiRED’s Iraq program, Dr. Khalid facilitated our work in the Basra Center and then with our telemedicine program for his doctors. He helped our programs, yes, but he also helped me personally. On one occasion in 2004, as travel in Iraq was becoming precarious for everyone, but especially for Americans, Dr. Khalid arranged for me to travel five hours between Basra and Baghdad hiding in the back of an ambulance. Insurgents, at the time, were more likely to let an ambulance pass.

In 2008, I got word that in January Dr. Khalid answered the door to his home and was shot to death. Insurgents are reported to have claimed that he was too close to allied forces. He also was a leading medical figure who drew the respect of his colleagues, and for the insurgents in Iraq, that was enough.

Telemedicine Program

In addition to the computer centers WiRED developed a telemedicine program linking Iraqi and American physicians via satellite. Initially, it was a notable success, demonstrating the value of real-time, two-way communications, well before Zoom and Skype became household tools. Iraqi physicians in Baghdad, Basra and Erbil shared lectures with physicians from the Children’s National Medical Center (now called Children’s National Hospital) in Washington, D.C; the University of California, San Francisco; and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Nursing professors from San Francisco State University provided lectures with Iraqi doctors and medical students.

Despite the success of this real-time lecture program, challenges became overwhelming, and we were unable to sustain the information bridge for much more than a year. What happened? The big obstacle was the very high cost of satellite time, which was at a premium in Iraq. We found it increasingly difficult to raise the funds for bandwidth to sustain regular and stable connections. Beyond cost, these teleconferences required doctors to gather in one place, and with the growing violence throughout Iraq, especially against doctors, it became increasingly difficult to arrange lecture schedules. In Baghdad, for instance, doctors who would attend a teleconference at Medical City in the afternoon were forced to sleep on gurneys overnight or face the threat of traveling home after dark. And so a popular and beneficial education program was forced to close. I found that especially distressing because these connections provided not only an exchange of the latest scientific developments but they fostered an important relationship between doctors in Iraq and doctors in the United States. The teleconferences didn’t just offer education, they connected Iraq’s opinion leaders who would be critical in the country’s reconstruction.

Despite the success of this real-time lecture program, challenges became overwhelming, and we were unable to sustain the information bridge for much more than a year. What happened? The big obstacle was the very high cost of satellite time, which was at a premium in Iraq. We found it increasingly difficult to raise the funds for bandwidth to sustain regular and stable connections. Beyond cost, these teleconferences required doctors to gather in one place, and with the growing violence throughout Iraq, especially against doctors, it became increasingly difficult to arrange lecture schedules. In Baghdad, for instance, doctors who would attend a teleconference at Medical City in the afternoon were forced to sleep on gurneys overnight or face the threat of traveling home after dark. And so a popular and beneficial education program was forced to close. I found that especially distressing because these connections provided not only an exchange of the latest scientific developments but they fostered an important relationship between doctors in Iraq and doctors in the United States. The teleconferences didn’t just offer education, they connected Iraq’s opinion leaders who would be critical in the country’s reconstruction.

Final Thoughts

We’ve been out of Iraq for more than 14 years, and, at some level, I believe our work demonstrated what one of our board members, Dr. Richard Carmona, 17th Surgeon General of the United States, calls medical diplomacy, sometimes citizen diplomacy. Creating the medical information centers, bringing in the digital libraries and arranging Internet connections, all for the purpose of helping the struggling medical community, showed that the United States was about more than the battles that Iraqis saw in the streets and that Americans watched on the evening news.

I stepped out of a hospital in Baghdad one hot afternoon when a young boy, maybe 11 years old, threw me a salute. I was in a boonie hat and sweaty civilian clothes, clearly not a soldier. But, a civilian or not, the boy thought of all Americans as soldiers, and so he saluted me as he had seen the soldiers salute. Not to disappoint the boy, I returned the salute, but I wish I could have told him that Americans came to his country not only as soldiers but in other capacities, too. We were teachers, computer technicians, doctors and engineers. We came to provide assistance, because we wanted to help him and his family who had been living under a dictator’s thumb for years and were now suffering from deadly assaults in the streets.

I stepped out of a hospital in Baghdad one hot afternoon when a young boy, maybe 11 years old, threw me a salute. I was in a boonie hat and sweaty civilian clothes, clearly not a soldier. But, a civilian or not, the boy thought of all Americans as soldiers, and so he saluted me as he had seen the soldiers salute. Not to disappoint the boy, I returned the salute, but I wish I could have told him that Americans came to his country not only as soldiers but in other capacities, too. We were teachers, computer technicians, doctors and engineers. We came to provide assistance, because we wanted to help him and his family who had been living under a dictator’s thumb for years and were now suffering from deadly assaults in the streets.

I would like to have told him that I was a volunteer, working with many other American volunteers here and back in the United States who came together to show our support and to help where we could with health care, education and other basics. For us it was more than a job. No one paid us, we didn’t have to be here. We were in Iraq because we had some skills that we thought might help his country in some small way. I wish I had been able to tell him that. Instead I saluted him and went on with my work.

I have worked with WiRED’s volunteers over many years, and I am always grateful for their generosity and their genuine regard for people living elsewhere, under punishing conditions. With deep fissures in American politics these days, it’s often difficult to see that spirit in our population. These volunteers give their time, talents and money to assist populations beaten down by a despot, by war, hunger, disease and natural disasters. They don’t do it for money that drives so much of our culture, or for praise by the recipients, since most will never meet the people they’re helping.

I have worked with WiRED’s volunteers over many years, and I am always grateful for their generosity and their genuine regard for people living elsewhere, under punishing conditions. With deep fissures in American politics these days, it’s often difficult to see that spirit in our population. These volunteers give their time, talents and money to assist populations beaten down by a despot, by war, hunger, disease and natural disasters. They don’t do it for money that drives so much of our culture, or for praise by the recipients, since most will never meet the people they’re helping.

So, why do people volunteer? I never know, but I suspect that for some, it’s a plank in their religion. For others, it’s an opportunity to join a team of like-minded souls working toward a noble end. I’m sure for others it’s an effort to keep the balance of life’s blessings and curses tilting in their favor. WiRED’s volunteers, each for personal reasons, joined to help people around the world, and starting in 2003, they pitched in to assist Iraqi doctors and the Iraqi people.

Our Attention Turns to Ukraine

As I write this, a dozen volunteers are preparing a program to benefit the Ukrainian people. We will train community health workers (CHWs), using the core curriculum we have brought to countries in Africa, Latin America and Asia. In addition, we’re adding a significant training block on first aid and critical care, clearly a relevant topic in Ukraine, where civilians have been in the crosshairs.

For the first time, we’re also making the full curriculum available to everyone in the population, not just CHWs who go through formal classroom training. Why? We feel that a population is better able to withstand assaults on its health when more people have a basic understanding of the health challenges facing their population. WiRED’s volunteers are joining volunteers with other organizations to prepare the training program that will help prepare the citizens of Ukraine face the assaults of war with better skills.

For the first time, we’re also making the full curriculum available to everyone in the population, not just CHWs who go through formal classroom training. Why? We feel that a population is better able to withstand assaults on its health when more people have a basic understanding of the health challenges facing their population. WiRED’s volunteers are joining volunteers with other organizations to prepare the training program that will help prepare the citizens of Ukraine face the assaults of war with better skills.

Some of the People Involved in WiRED’s Work

I build my thinking about our work in Iraq around the people who played a role in our programs. Some I have already mentioned: Steve Browning, for instance, was a valued coach who provided us with opportunities that allowed our work to move forward quickly.

Pen Agnew, is an official at the State Department who saw our work in Croatia in the late 1990s and paved the way for other programs in Bosnia, Montenegro, Serbia, Albania and Kosovo. Early in 2003, Pen asked if I would consider using lessons learned in the Balkans for a project in Iraq. He connected me with Jim Mollen. Since WiRED left Iraq in 2009 I have occasionally asked Pen for his advice on various issues. He is a diplomat who understands that addressing the needs of ordinary people is an effective element among the tools to establish better relationships abroad.

Jim Mollen, the State Department official I traveled with and roomed with in Saddam’s palace, paved the way for me to coordinate my work in Iraq with State Department officials in Washington. Before I mention the names of other people, I need to relate a story about Jim’s death.

More than a year after we arrived in Iraq and our programs were advancing pretty much on schedule, I needed to deal with an issue for another WiRED project in Kosovo. I flew to Pristina, the capital, and a day after arriving, I got an email from Pen Agnew, a Planning Coordination Officer in the Office of Press and Public Diplomacy. It was Thanksgiving Day, 2004. Pen wrote that a day earlier Jim was shot to death while traveling in a car just outside the Green Zone. Insurgents knew Jim’s schedule and apparently lay in wait for him. As the U.S. Embassy’s Senior Consultant to the Iraqi Ministers of Education, Jim had been making significant progress using computer technology to improve the education system. Success put a target on his back. In an official statement, Secretary of State Colin Powell said Jim’s, “sacrifice and heroism embody the greatest American virtues.” Jim was one of the civilians who eagerly put his shoulder to the cart in Iraq.

It was Pen’s next question that brought me back a year to an incident in Iraq: Do you have a photo of Jim?

In the summer of 2003, Jim and I took a 50-mile trip from Baghdad to Babylon to attend a meeting. We had a two-hour break, and so we decided to explore the ancient ruins, the archaeological sites once part of Nebuchadnezzar’s empire. Jim was standing in the middle of a crumbling section of an ancient structure and shouted for me to take his picture. Jokingly, I shouted back that snapping his picture would ruin my camera. Then I snapped the photo and forgot about it.

It was when Pen asked if I had a photo of Jim that I thought about that afternoon in Babylon. Apparently, someone needed a photo for Jimi’s obituary, and I had one of the few around. I found the image on my laptop and attached it to an email. I could never have imagined a year ago, standing among the ruins of Babylon, that the casual snapshot Jim asked me to take would serve in his obituary.

Dr. Miriam Othman, M.D., M.P.H., is a physician who worked for the International Organization for Migration (IOM) at the time I arrived. Miriam helped me connect with the Iraqi Ministry of Health and other agencies, and she introduced me to her colleagues at IOM. Miriam always impressed me as a bright, level-headed young physician who knew her medicine and kept her cool under fire. I saw that on a trip to Amman, Jordan, one day when we had a close encounter with a firefight between insurgents and American Marines. That’s a story for another time.

As with many doctors in Iraq, Miriam was warned at gunpoint to leave the country within 24 hours or be killed. It was not an idle threat, and she knew it. She escaped to Dubai and eventually came to the United States by way of a Fulbright scholarship to earn her M.P.H. at George Washington University. Today, Miriam teaches medicine in California and serves as WiRED’s medical director. She has been the author of many of our health modules that have trained hundreds of thousands of people around the world. Miriam has been an outstanding colleague, and she has become a good friend.

Che Pangborn is a husky, good-spirited and brilliant computer technician whom I met in Kosovo. We worked on computer projects for a year or two in other Balkan countries and then, in preparation for a large health program in Kenya, Che helped train several dozen young people in Nairobi how to operate computers. Che enjoyed the adventure, and he was eager to help us. So, without much convincing, he came to Iraq to set up our first MICs.

As I described elsewhere we obtained the first 12 computers for Medical City Center from a vendor who safeguarded his inventory in a secret barn outside Baghdad. Che verified the quality of the computers, and then joined me in finding networking equipment, cables and connectors and the other items needed to build a computer lab. Despite the heat and traffic and endless dinners of Meals Ready to Eat and the shortage of everything, Che remained the most upbeat and optimistic person I’ve ever met.

When Che and I needed to travel to dangerous places around Baghdad, an American Army captain, George Guszcza, took us under his protective wing. He would drive us and keep an eye on us. Che and I weren’t armed, so it wasn’t a bad idea to travel with someone who was. George later left the Army when his tour was up, but we stayed in touch. In 2010 he accepted our invitation to join WiRED’s board. Also that year, he went to Oxford University for his master’s degree.

In the northern Kurdish region of Iraq, Dr. Lezgin Chali, a physician, became the engine behind our work to install medical information centers in Erbil, Sulaymaniyah and Duhok. Dr. Lezgin was an official in the government of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq who had a passion for anything related to medical education and computer technology. He was naturally drawn to our project which involved both. Dr. Lezgin also had an abiding interest in philosophy, music, literature and politics. His interests read like the index of the New York Times. Some colleagues of his called him the doctor philosopher. Without his coaching and support, we would not have been able to advance our work in northern Iraq.